Gift

poems and stories

scroll down to read poems and stories in our

Winter Theme

growing weekly from December to February 2020

meet the poets and writers

Kerry Darbishire

Shanta Acharya

Lizzie Ballagher

Peter Burrows

Rachel Beresford-Davies

Matt Barnard

Michael Brownstein

Alan McCormick

Anna Saunders

Dorothy Burrows

Keith Tucker

Kathryn Bevis

Allen Ashley

Claire Booker

Gordon Peters

Hilaire

Kate Young

Buffy Shutt

.

Xaioly Li

.

Gift

Our first poem for winter is by Kerry Darbishire

Kerry Darbishire, songwriter and poet, grew up in the Lake District where she continues to live, find inspiration and write in a wild area of Cumbria. Her poems have appeared widely in anthologies and magazines and have won or been listed in several competitions, including the Bridport shortlist 2017, and the 2018 PBS Mslexia Poetry Competition. Her first poetry collection, A Lift of Wings, was published in 2014 by Indigo Dreams. A biography, Kay’s Ark, the story of her mother, was published in 2016 by Handstand Press.

Her second poetry collection, Sweet on my Tongue, was published by Indigo Dreams in 2018 and is a finalist in the Cumbria Culture Awards 2019. She co-edited the new Handstand Press Cumbrian Poetry Anthology, This Place I know. Kerry is currently working on a pamphlet and a new full collection.

Kerry Darbishire – A Winter Gift

A Winter Gift

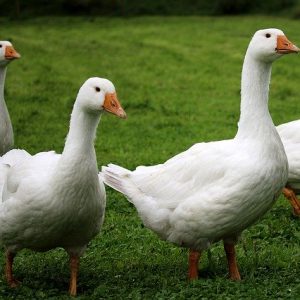

If the eggs didn’t nudge each other

in the blood-warm bucket of water and they floated

to the top, we took them out. I watched twelve

out of fourteen fidget then sink like mint-white pebbles.

That first January

our present of two geese and a gander

from a farm on the coast, panicked over hedges –

flapped their new wings into Peter’s field

as if migrating until we caught them

and they softened like air in our hands.

Amber beaks clattered, sapphire eyes pinned

the beginning of a story we hugged into a shed

of fresh straw. Henry, Gertie and Lucy discovered the river,

bagged the best lawns and on Valentine’s day,

slipped moonshine eggs like secrets into caskets of down.

Henry became a queens’ guard outside the sanctuary –

dressed in hissing armour, neck to the ground

patrolling inside to tuck in loose straw and roll back runaways

before they cooled. For twenty eight days they processed

to the river to drink, dampen breast feathers,

tend their caches while we prayed for no thunder to addle,

no drought and no hungry foxes. Come early May

our garden rolled in yellow like curls of butter over green plates.

Our years of scattering grain, opening and closing

their warm mornings and frosty nights slowed

until all they could do was trust and warn us of strangers.

Now in silence, grass grows undisturbed – even the river

seems less useful and my cakes are pale. On winter nights

I reach into the cupboard inside a dark box tissue-soft

and unwrap blown undecorated Fabergé.

Kerry Darbishire

Letters from Home by Kerry Darbishire

Kathryn Bevis is an emerging poet and educator. She read English at St Hilda’s College, Oxford, and is founder of The Writing School in Winchester. Kathryn hosts a Poetry for Wellbeing project for service users of the charity Mind, funded by Arts Council England. Recent awards include being shortlisted for the Nine Arches Press Primers Scheme, winning first prize in the Poets and Players competition, third prize in the Welshpool Poetry Festival competition, and runner up in the Out-Spoken Prize for Poetry.

Kathryn Bevis – Devil Day

Devil Day

Our ending happened as a gift. That day

the change blew through us. A shudder-flood

of starlings flung away like iron filings

while we gripped the path, jackets billowing,

hair full sail. Even the features of your face,

grim-set against the wind, threatened

to unmoor. We flattened our feet upon

the track as thorns thrashed into new shapes

against a damaged sky and the coconut scent

of warm gorse faded on the air. At the peak,

great lumps of basalt, torn from the hills

some other devil day, lay hurled about.

The wind whirled in the coves of our ears

to make them into echo chambers,

casting our voices off elsewhere,

sending thought to unspoken places.

All at once, each flailing thing was stilled.

We faced each other. Not a word. We knew.

As you scrambled, separate, down the scree,

the heather foamed, on fire beneath my feet.

Kathryn Bevis

Shanta Acharya was born and educated in Cuttack, India. She won a scholarship to Oxford, where she was among the first batch of women admitted to Worcester College in 1979. A recipient of the Violet Vaughan Morgan Fellowship, she was awarded the Doctor of Philosophy for her work on Ralph Waldo Emerson. She was a Visiting Scholar in the Department of English and American Literature and Languages at Harvard University. The author of eleven books, her publications range from poetry, literary criticism and fiction to finance. Her latest is Imagine: New and Selected Poems (HarperCollins, 2017). ‘Possession’ is from her forthcoming collection, What Survives Is The Singing. www.shantaacharya.com

Shanta Acharya – Possession

Possession

When I lost something valuable,

I gave it a name, inscribed it on a pebble,

piece of wood, paper, cloth or shell,

placed it in my handbag, let the words settle

in with the rest of my losses defining me –

keys to my anxiety and loneliness,

notebook and pen to record panic attacks,

iPhone, lipstick, comb, cards calling for attention,

tissues folded in cellophanes of adjustment –

carrying on with my chores as if nothing

was the matter, clutching my grief

like a mascot, trying to transcend

that feeling of things missing, life passing,

shrinking, until disappointment rushes in,

weighing me down with further losses,

and my bag too heavy to hold my dreams,

complains this is no way to treasure

hard-earned gifts enriched by dispossession,

awaken to the true nature of being,

no longer be defined by this or that.

Shanta Acharya

A published novelist between 1984 and 1996 in North America, the UK, Australasia, Netherlands and Sweden (pen-name Elizabeth Gibson), Lizzie Ballagher now writes poetry rather than fiction. Her work has been featured in a variety of magazines and webzines: Nine Muses, Nitrogen House, the Ekphrastic Review, South-East Walker Magazine, Far East, and Poetry Space.

She lives in southern England, writing a blog at

https://lizzieballagherpoetry.wordpress.com/.

Lizzie Ballagher – Fieldfares

Fieldfares

In a long-shadowed corner of this orchard

the farmer has emptied barrel-loads of fallen fruit;

my father might well have done the same—

I wish I could recall.

He was a blackcurrant farmer,

A man who also loved wild birds.

His keen spirit stalks us in the sharp wreckage

of winter prunings; in the branch boneyard

where cherry trees are skeletons of their summer selves;

where decomposing, dappled pears send out tendrils

of fragrance into frost-pinched, ice-pearled air

and snare the fieldfares as they pass.

Above our heads fat crab-apples hang:

jewels on the bulbous ropes of aged branches,

priceless rubies on a sapphire sky.

A single fieldfare rises, topaz speckled,

white underwings in chevrons, her back

gleaming garnets in the horizontal light.

She turns, flings skyward with her diamond beak aimed

unswerving at the apple sun.

The flock explodes—twelve, twenty, two hundred birds

all mocking frost on hoar-bleached branches;

all celebrating the farmer’s luscious gifts,

chuckling with glee over winter windfalls.

Lizzie Ballagher

Rachel Beresford-Davies grew up in Hong Kong and has since lived in London and the south of England. She has two science degrees and is currently studying for an MA in Creative Writing at the University of Winchester. She has been writing for many years but mostly kept it to herself. In the last year though she has had short stories published through Fairlight Books and Literally Stories. Her writing is mostly inspired by the everyday and commonplace events she observes in her mostly everyday and commonplace life.

Rachel Beresford-Davies – Satsuma

Satsuma

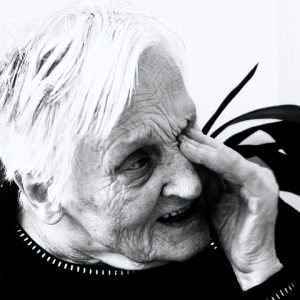

Mother is sitting on her sofa peeling a satsuma or clementine, or some other small, orange citrus fruit. She has removed the skin in small, fingernail-sized pieces, and is now carefully detaching quivering strands of pith, and placing them with precision next to the teetering pile of skin on the arm of the sofa. I will be clearing it off later.

After removing as much of the pith as she is able she will eat the satsuma or clementine or whatever it is, chewing each individual segment with the three teeth she has left in her mouth and extracting the juicy orange flesh from inside the translucent membrane with her tongue. Then, one by one, she will remove the fleshless membranes from her mouth and place them with the pile of skin and pith.

When she has finished this process, which normally takes around thirty minutes, she will sit for a time, turning now and then to look at the pile of skin, pith and membranes, perhaps rearranging them a little. Very occasionally she will carefully gather the pile of detritus and place it on the coffee table in front of her, where she will sit for some further time, regarding it judiciously.

Eventually, she will shuffle forward on her seat, and with some effort stand up and walk over to the fruit bowl where she will spend some moments selecting another small, orange citrus fruit. Thus the entire process will be repeated, ad infinitum should the fruit supply allow.

I have learnt to pace the small orange citrus fruits. Four for the morning, four for the afternoon, or occasionally, on a bad day, five. None for the evening. In the evening she will doze, lulled by the clatter of family life and television drama. But during the day, it is just her and I, and neither of us sleep.

She has eaten the final fruit of the afternoon and is agitated. It is only 4 o’clock. There are countless more small, orange citrus fruits, hidden under the stairs. Her netted pacifiers. Glancing up now and then as I tap at my computer, I silently observe her, hovering beside the fruit bowl, now and then grasping one of the apples before putting it back. She cannot eat apples, her three widely spaced teeth will not allow it. She knows she cannot eat apples, yet she doesn’t know who I am.

I sigh, and look past her, fixing my gaze out of the window on the disordered back garden. The grass is barely visible, covered with an untidy blanket of fallen leaves in russet and yellow, making the lawn look like an unmade bed. Every now and then the wind whips up and swirls them in circles, depositing them again a few feet from their last resting place. They seem to have caught mother’s attention too and she turns her frown from the fruit bowl to the window, making small, indecipherable sounds. I go over and stand next to her for a while, hoping to calm her agitation, and together we watch the leaves dance soundlessly about. Eventually though, her sounds become more urgent and threaten to become something else. I gently take hold of her arms.

“Come and sit down mum. Do you want a cup of tea?”

Her previous cup of tea stands untouched on the lamp table. But then, there were satsumas. Now, there’ll only be tea. It might work.

She submits and allows me to guide her back to the sofa, still mumbling. She sits for a while, her hands fidgeting in her lap, casting confused looks at the fruit bowl.

Suddenly, she turns her head towards me and says, clear as a bell,

“Where’s Gerald?”

She does this sometimes. It is as if somebody has flicked a switch in her brain causing random connections to be made. They will sputter out again soon enough, but I always enjoy her rare moments of apparent lucidity. This one though is unexpected, and for a moment I am floored. Gerald – my father, her husband. Gerald, who cared for her, clearing away the endless piles of satsuma peel, finding them in unlikely places. Gerald, hollowed out from the loss of our family’s anchor, chuckling as he reported her antics.

“I found a pile of peel in the fridge the other day,” or, “she’d managed to tuck some down behind the cistern. I mean, why does she need to hide it?” And we’d laugh, tears pooling in our eyes. Together we mourned who she had been and tried to seek comfort in what she had become. “She’s as strong as an ox, your mother, she’ll survive all of us,” he’d said after her diagnosis, “trouble is, it’s your heart that keeps you alive, but your brain that keeps you living.”

It was the former that finally claimed him, leaving me the sole clearer of satsuma peel. I stir mother’s tea and take it over to the sofa, collecting the waste paper bin en route. Mother is still looking at me, but I can see she has already forgotten her question. “What did you say, mum?” I ask, just in case, placing the cup of tea next to her. She frowns and turns her gaze slowly on the fruit bowl. Once again, she begins to shuffle forward on her seat. I scrape the satsuma peelings from the arm of the sofa into the bin, watching them fall among the accumulated others, slowly rotting at its base. They are like the fragments of her brain. Disease-ravaged, being whittled away, cell by cell, with every satsuma she eats.

I turn on my heel and head to the cupboard under the stairs, extracting two bags of satsumas. The netting cuts into my fingers as I rip them both open, and tumble all sixteen small, orange citrus fruits into my mother’s lap. “Do your worst, mum,” I say. She looks down, and just for a second or two her face is lifted by something that could almost be joy.

Rachel Beresford-Davies

Peter Burrows is a librarian in the North West of England. His poems have appeared most recently in Marble Poetry, Northwords Now, Dream Catcher and Coast to Coast to Coast. His poem ‘Tracey Lithgow’ was shortlisted for the inaugural Hedgehog Press 2019 Cupid’s Arrow Poetry Prize and appeared in the Cupid’s Arrow Love Poem Anthology.

peterburrowspoetry.wordpress.com

Peter Burrows – Three poems

The Unseen

Lying in the bath with the door ajar

I hear her voice clear in the next room settling,

chatting away, sounding out fragments of song,

and, as so often now, I think of you.

Was it like this for you with us? Smiling

off-stage: from infant to adolescent,

soft cooing to lofty pronouncements?

What did you think when you were lying there

absorbing that sudden sentence that floored

us all. ‘I won’t see his family’, you replied.

What if I’d sat beside you, vague hopes shared,

names we might’ve chosen you could repeat,

and I’d say how I’d love them like you loved us.

But those first choices would just be empty hints

and would it matter if you saw a future

false, like I search for this dream of a past?

Is there comfort in the touching distance

of your loss at the first steps of one year,

her arrival at the end of the next almost

beside each other like your name within hers,

and our last years striving somehow to connect?

We could have cherished, entrusted in the link

beyond the given bond of shared blue eyes.

Now a father, I see and feel more like you

than I ever knew; all you did, in the days,

and nights, the unseen love – the faith to live

knowing you won’t see the full story with

those you begin it by. It’s in gestures

we are remembered. How you were with us.

The life given; each gift time brings. The songs

you sang to me – the same songs that she now sings.

Peter Burrows

First published in The Cannon’s Mouth, March Issue 2017

The Craft

When in search for something to make my own,

daydreaming self-worth with nothing but air,

how oblivious I was to your home-grown

craft. From youth, your needles never stopped

clicking; that comforting homely rhythm.

Colourful patterns, loose threads strewn by your chair.

Each day always making, always giving

for tomorrow: baby clothes, thick winter

blankets we now hide under; or soft

nativity toys we bring out each year.

What appeared everyday was made to last.

So, when you rallied, your resolution encompassed all.

Despite hope gone, your last day come, still you asked:

Tomorrow, would we bring your needles and wool.

Peter Burrows

First published in ‘Word Life’: Now Then, Manchester (online), ‘Hope’ issue 52, March 2018, and in Bonnie’s Crew (Autumn 2019).

First Spring

You equipped us with pens and paper, not just

to keep us busy on long journeys, but to share

your own delight spotting nature. Birds. Rabbits. Deer.

The other hidden lives that surround us.

Yet years later, crossing the high border plains

battling the last rage of a week’s winter’s gales,

our swaying car passing overturned trucks,

we trailed blinking-wet brake lights, seeing nothing.

But on reaching you the wind dropped. Becalmed.

Numbness befitting those first days, sleepwalking

the long, dulled-glass corridors overlooking

the distant estuary, to your blinds-shut room.

No horizon. And within days you were gone.

We quietly retreated South. Routines resumed.

Passers-by in their own lives didn’t know

or care. Held hostage to our senses.

Curtains drawn. Missed calls. Cocooned reactions.

Divisions. Darkness. Darkness. All was loss.

It seemed an age. But out there, light’s gradual reach

thawed the ground to a misty breath. First, snowdrops

nudging through. Birds, skittish, hungry, unseen.

It must have happened because now, here we are:

the sky, a bright and brittle smarting blue.

The air a claw grip achingly unfolding.

But still too sweet, too soon; embattled, winter-braced.

What’s it all for, if not seen by you?

Days must be lived in. What else can we do?

First spring, then remaining seasons must come.

Remembering you anew with each altered one.

The first lambs are born. Let us count them for you.

Peter Burrows

First published in The Eildon Tree, Spring 2018.

Hilaire is co-author with Joolz Sparkes of London Undercurrents, published by Holland Park Press. She was poet-in-residence at Thrive Battersea in 2017, and has poems published in numerous magazines and in three anthologies from The Emma Press.

For the London Undercurrents blog:

https://londonundercurrents.wordpress.com

Hilaire – daily dose

Kerry Darbishire, songwriter and poet, grew up in the Lake District where she continues to live, find inspiration and write in a wild area of Cumbria. Her poems have appeared widely in anthologies and magazines and have won or been listed in several competitions, including the Bridport shortlist 2017, and the 2018 PBS Mslexia Poetry Competition. Her first poetry collection, A Lift of Wings, was published in 2014 by Indigo Dreams. A biography, Kay’s Ark, the story of her mother, was published in 2016 by Handstand Press.

Her second poetry collection, Sweet on my Tongue, was published by Indigo Dreams in 2018 and is a finalist in the Cumbria Culture Awards 2019. She co-edited the new Handstand Press Cumbrian Poetry Anthology, This Place I know. Kerry is currently working on a pamphlet and a new full collection.

Kerry Darbishire – Bringing in the Shrimps

Bringing in the Shrimps

When the ground crunched like shells

and breath hung still as a frozen cloth

Les knew it was time. A man of land and sea

– ate only what he could carry.

Come on lad, he’d call

pulling my man from warmth into the November night

to drive along the bare coast road where people had done

with walking for the day, where trees curved

like net-mender’s hands.

Into the sift of salt-white pebbles they marched

abreast of the tide pressed dark far beyond shifting sands

and where the sea held its breath

set their nets on the bar.

With half an hour to scrape shoaled gullies – timing the turn

just right then back with a catch of phosphorescence

– a mass of heaven

steering into the bite.

We laid white sheets in the moon-shine yard, set wide pans

of water on the stove. My children woke soft-eyed and

wrapped in blankets to watch the sacks of grey turn pink-gold

in the boil – a spread of ancient tender swilled onto linen.

Kerry Darbishire

Decades ago, Dorothy Burrows taught Drama and wrote short plays and the occasional short story. She won a few awards. After years of working in a museum, retirement is enabling her to enjoy creative writing again. Walking in the countryside often gives her ideas for poems, especially haiku. She attends poetry classes tutored by Elaine Baker.

Dorothy Burrows – Skirt

Skirt

Tipping out an old brown suitcase,

I find you have left me your skirt.

It was a best skirt too: worn mainly

for village fetes, Sunday School shows,

set-menu dinners on coach holidays

to Ilfracombe, Lyme Regis, Inverness.

Pure polyester; so easy for you to throw

in the twin tub, your rock ’n roll spin-dryer

then hang out with dolly pegs on the line

amongst rhubarb and goosegogs to dry.

Once, sea breezes whipped up and blew it

across our field full of Friesian bullocks;

you battled through grass and cow pats

with a long yard-broom to bring it back

to scrub again with Lux soap flakes

and typical feistiness in the scullery sink

before wringing it, pegging it out afresh

with three extra pegs for good luck.

Your skirt held fast to the line this time

whirling, flapping in the Westerly wind;

bright, loud, agitated, strong; an exotic bird

crash-landing on a patch of marshland

at Lancashire’s edge. Your skirt’s patterns

in green, orange, blue, look vivid even now

against the grey; its synthetic sheen is still

silky smooth forty odd years on. Let’s face it,

this skirt was not worn much. It wasn’t done

for folk like you to shock in-laws, neighbours,

and the village set with a flounce of urban chic;

But did it ever look chic on you? Is that why you

left it in the case? So I would wash it, wear it;

breeze into arty parties, like you never could?

Dorothy Burrows

Anna Saunders is the author of Communion, (Wild Conversations Press), Struck, (Pindrop Press) Kissing the She Bear, (Wild Conversations Press), Burne Jones and the Fox ( Indigo Dreams) and Ghosting for Beginners ( Indigo Dreams). Anna is the CEO and founder of Cheltenham Poetry Festival. She has been described as ‘a poet who surely can do anything’ by The North and ‘a poet of quite remarkable gifts’ by Bernard O’Donoghue. Anna’s forthcoming book is called Feverfew. ( Due Indigo Dreams Summer 2020). The collection has been described as ‘ rich with obsession, sensuousness and potency’ by Ben Ray and ‘a beautiful and necessary collection’ by Penny Shuttle.

Anna Saunders – Time after time the same bird is born from the flame

Time after time the same bird is born from the flame

Here it comes, shedding embers as it struts

a feathered doppleganger of the last,

an identical gold-eyed genesis

scattering a surplus of silver plate from its claws

shaking down the same, ornate feathers of over ripe-hue

(deep as a peach skin gone to the bad).

Each day we pick at seeds and stringy meat

as the royal bird feasts on incense

buffs its salamander scales with silk.

How did it earn the spokes of sun that ascend from its head,

the nimbus that blazes like a cloud backlit by the moon?

We ache for change, yet each creature that rules the court

is a rooster’s brother with jaundiced eyes.

Not even death will bring an end to this.

The purpled bird stains the air

like dye bleeding through cotton.

Golden swan – you entombed your father

in a burning planet,

emerged yourself empowered.

How wrong we are to think that fire

can cauterise corruption.

Time after time the same bird is born from the flame.

We watch him rise on ash wings

singing as he buries the sun.

plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose

Anna Saunders

Alan McCormick lives with his family by the sea in Wicklow. He’s been writer in residence at Kingston University’s Writing School and for the charity, InterAct Stroke Support. His fiction has won prizes and been widely published, including in Best British Short Stories, Confingo, The Bridport Prize anthology, and online at Words for the Wild, 3:AM and Epoque. His story collection, Dogsbodies and Scumsters, was long-listed for the 2012 Edge Hill Prize.

He also writes shorter pieces, known as Scumsters, in response to pictures by artist Jonny Voss. See more of this collaboration, along with Alan’s own fiction at www.alanmccormickwriting.wordpress.com

Alan McCormick – The Star Shaped Scar

The Star Shaped Scar

It’s night. I’m lying on the sofa and the wind howls through the red clapperboard fisherman’s hut Mum has always called home. The timber frame creaks, there’s a scurrying of blown sand, and I can hear crabs scraping and burrowing under the floors.

I haven’t been up to Scotland for a year and in that time so much has changed. Her face, always so ruddy and strong lined, looks pinched, yellow somehow, and her long sandy hair is now overrun with grey. And I’m not sure if it’s possible but she seems to have shrunk, her once sparkling, mischievous humour blown away. I’ve been here a few days and she hardly sleeps, is always on the move throughout the night, scattering pills, scratching at her self, muttering into walls.

I’m woken by something banging down below. I get up to investigate. The light is on in the kitchen and I can hear her talking:

‘Must get the clock fixed, send old Robbie his cheque, get my boy his milk!’

I feel heat come into my cheeks and I don’t know whether I’m angry or just embarrassed; Mum is naked, wild eyed, the window above the sink banging open and shut on the icy rushes of wind.

‘Oh, Alex, I didn’t hear you. Is it time for school already?’ she says, her voice suddenly calm, matter of fact. ‘Let me heat up a pan and make you a hot drink.’

I feel ashamed that I haven’t visited her more but I’m also ashamed of her, of how she’s become. She walks towards me and I don’t want her to get too near.

‘No, Mum, I’m okay. But I think we should talk.’

I cover her with my dressing gown.

‘Yes, yes, but let’s have a drink too,’ she says.

We sip our drinks together at the table not speaking. Then she says she’s tired and needs to sleep. As she gets up she stumbles and I see her scar again, only it looks purple and angry.

‘Mum, your scar, it looks really bad.’

‘What scar?’

‘The one on your ankle. The one you got on the beach.’

‘I got it from a shoe buckle, not from the beach,’ and she kisses me on my head, saying ‘you won’t forget the light, son.’ Then, as if on automatic, she clicks it out anyway and closes the door behind her.

I sit in near darkness, the pale blue flame of the hob burner for company (she’d forgotten to turn it off). Above her ankle my mother has always had this distinctive star shaped scar. I’d forgotten about it while I’d been away but I’d noticed it again yesterday morning. She was moving away from me, a pan of thin porridge griped in her hand, treading on the worn heels of her slippers, seeming to slide rather than step. I asked her to tell me the story of how she’d got the scar, a story I’d heard as a child many times before but each time in a different way. This used to be our entry to a shared imaginative world, our spinning of family myth and lore. Yesterday was no exception, just more elusive. By way of explanation she stood over the sink, looked out of the window at the wide stretch of sand and sea, and pointed.

Days later and the sunset over the beach is unpeeling a wound, the sea smeared in yellows and reds. We’ve got back from the funeral. A burial at sea is a terrible thing, the most cold, dismal experience imaginable; I’ve only just stopped shaking. I’m sitting with my sister in the kitchen at the small metal table I’d sat with my Mum only days before. The rest of the mourners are huddled in the lounge. We’re drinking brandy and hot milk. It’s the first time I’ve been alone with Therese for years. She looks lost and tired, and so I lie to her:

‘You were always in her mind, Therese, she never stopped talking about you.’

She starts crying and I feel numb, held in, like a child sleeping under a heavy duvet.

‘I hadn’t rung her for ages,’ she says.

‘She knew how much you cared . . . ’ and then I change the subject: ‘you know the scar above her ankle, she came up with another story about it before she died.’

‘What? What are you taking about?’ She sounds irritated, as if I’ve just stirred her from a dream.

‘She said it was caused the buckle of a new shoe but she didn’t say any more. It made me fantasise about the kind of shoe that might have caused it; like she’d been a glamorous fifties swinger, a femme fatale who danced the night away in a pair of exotically buckled, tight new dance shoes that an admirer had just bought for her.’

Therese isn’t listening, and takes my hand and strokes it up and down intensely like she’s worrying on beads:

‘Alex, Mum didn’t suffer too much, did she?’

Then she cries again, big quaking sobs this time, her features erupting, re-arranging themselves. I feel the shakes into my chest, bruising deep inside, but I’m still in my head and can’t let go.

We both fall quiet and listen to the wind against the windowpane, both remembering Mum in our own way. I think of her a few days before, looking out, pointing, and I break our silence:

‘I think I’ll stay on for a few days.’

Therese kisses me on the head as Mum had done the other day.

‘She would have liked that, Alex.’

I get up and rest my hand on her shoulder for a moment and then go to see how the other mourners are getting on. There are glasses to fill, and maybe more stories to hear.

Later that night I go for a walk on my own. The moon, generous and round sends waves of soft yellow light to glisten onto the slow moving sea. As I walk I pick up shells, feeling and examining them, before dropping a few chosen ones into my pocket. In the shallows where the water lies still and translucent over a narrow trough of sand, there is a small starfish. I gaze at it for ages and then bend down to pick it up. As I do it leaves its perfect grainy outline, its lifetime’s mark from the deep, in the sand. The top surface is rough and callused like an old scab but underneath it’s pearly, milky-white, smooth like ivory. I run the tips of my fingers on its cool underbelly and feel tears, hot tears, salty and stinging, run down my cheeks. I carefully place the starfish back into its imprint in the sand and notice the harsh top layer has cut my skin. Blood drips from my finger and swirls like oil into the shallows.

As I walk back to the house I think about what Therese had said before she left: how Mum first had cancer when I was really young and that her mythical scar came from a simple operation to remove a malignant mole. No one had ever told me story before. I find myself looking up at the sky at a lone northern star glimmering vainly on the horizon. I stare for a moment, then shut my eyes and think about the words I’ll use to tell Therese about the emptied bottle of sleeping pills and Mum’s last, secret late night drink.

No need for any more stories, I just want to get back into the warm, heat up a pan for myself and go to sleep.

Alan McCormick

Reasons to Swim Inside the Sky by Alan McCormick

Wish You Were Here by Alan McCormick

Zoe Brooks is a Gloucestershire poet. Indigo Dreams Publishing will be publishing Zoe’s first full collection “Owl Unbound” in 2020. She has had poems published in a wide variety of magazines, most recently in Obsessed With Pipework, The Curlew, Dreamcatcher and The Dawntreader. Her long poem for voices “Fool’s Paradise” received the Electronic Publishing Industry Coalition’s award for best poetry ebook 2013.

Zoe Brooks – Cleeve Hill

Cleeve Hill

I found you tiny stars

in the scree of a quarry scrape.

Broken fragments of echinoid stems

sat in my palm

no bigger than breakfast cereal.

Below us an ancient ring ditch

still sheltered the flock,

above us a hawthorn scratched

at clouds with arthritic hands.

The sky roared by

as you said you would make

a necklace of them,

and told me I had fossil eyes.

Years later, after your death,

I found a stone heart

in the shelter of the dip slope

and placed the fossil urchin

above the portal of the tump

where you had lain

on sheep-cropped grass

and said there was no better place.

Zoe Brooks

Chris Hardy has travelled widely and after many years in London now lives in Sussex. His poems have been published in Acumen, Agenda, Stand; Pennine Platform; Tears in the Fence; The Interpreter’s House; The North; The Rialto; Poetry Salzburg Review; Poetry Review, ink sweat and tears, the blue nib, the compass magazine and many other places.

He is in LiTTLe MACHiNe, performing their settings of poems at literary events in the UK and abroad. ‘The most brilliant music and poetry band in the world’ (Carol Ann Duffy).

His fourth collection, Sunshine At The End Of The World, was published by Indigo Dreams. Roger McGough said about the book, ‘A poet as well as a guitarist Chris consistently hits the right note, never hits a false note’ and Peter Kennedy, in London Grip says, ‘Chris writes vivid, expository poetry often heavy with portent and mystery. Each of these poems is as beautifully muscular and slippery as an eel’.

Chris Hardy – War Paint

War Paint

The girl in Belsen thought she was dead,

until an English boy who’d never been

to France or Germany,

never asked to leave his Mum

and sisters back in Kirkby,

to run down lanes while someone

shot at him, threw bombs on his head,

came through a gate and gave the girl

in stinking rags who couldn’t walk,

a dish of porridge, a drink from a flask,

and a tube of lipstick red as blood,

glistening and perfumed.

Chris Hardy

Harriet Jae – Sea gift

Sea gift

Waves of a swelling ocean,

our fathoming bodies move –

your hips, my answering shape

motion a heady storm.

Shoals of tiny silver fish

flutter through us

and somewhere

an anemone blossoms, unseen.

In the sway of the sea,

our seaweed limbs

caress, relinquish, cling,

tendrils of helpless compliment.

How far would the storm reach?

In a lost moment,

silk ropes entwined our minds,

our fingers prised

the hinges of time and space.

Wrecked and barnacled treasures

(so long, so deeply drowned)

stirred in the shifting seabed,

lit by brief lightning.

Far from you now,

castaway in the sun

on this windswept shore,

I long to tell you:

I see now that each wave

begins to soften the rocks,

each yearns for and transforms the sand.

Some leave gifts

of driftwood, shelljewels, starfish.

Harriet Jae

Keith Tucker is an Oxfordshire based poet who through the mentorship of Elaine Baker has returned to poetry after many, many years in the creative wilderness. Because of his Anglo-Welsh-Canadian background a lot of Keith’s work explores identity and belonging as well as relationship and intimacy. In his day job he supports adults with autism and learning disabilities to use poetry and creative writing for self-expression, communication, and advocacy.

Keith Tucker – Nesting

Nesting

you created us by way of nesting, gifting

the place where you are now;

the two-seater sofa a twig in your dove mouth.

emptied three bookshelves that I may roost

the freight of my being when the boxes arrive.

neither of us a songbird, nor caged canary,

nor lark homesteading a downland, yet

you made spaces to merge our songs,

my jazz brooding beside your Beethoven.

photographs hang as blossoms from your life,

you left picture hooks waiting, buds for memories

yet to be agreed. And I embrace your gift

as I embrace the optimism of the half

full wardrobe.

Keith Tucker

Claire Booker lives between the sea and the south downs near Brighton. Her pamphlet Later There Will Be Postcards is out with Green Bottle Press and a second is forthcoming with Indigo Dreams Publishing. Her poetry has appeared in magazines including Ambit, Magma, The North, Rialto, Standand The Spectator, as well as been displayed on Guernsey buses, filmed by Aberystwyth University and simultaneously performed at six venues during the 2019 Solstice Shorts Festival. Last year, she received a Kathak International Literary Award in Bangladesh where she was guest poet at Dhaka’s International Writers Festival. Her website can be found at: www.bookerplays.co.uk

Claire Booker – New Arrival

New Arrival

I could breathe in each last lash of him.

Fatness of fingers half furled,

smell of shelled peas –

such is the feel of new pricked dough

lightly brushed with milk.

That sly slant of eye hoards a foreseeing

loose of words or knowing.

He does not dream as I dream now

but as a sill gathering drops,

a dome’s dark space absorbing whispers.

The lazy crescent moon, tipsy

on a bellyful of night, is hammocked

in winter branches. I’ll watch the sky roam

panther black, count stars as sheep,

not close my eyes for disbelieving.

Claire Booker

Allen Ashley is President Elect of the British Fantasy Society. His most recent book is the poetry collection Echoes from an Expired Earth (Demain Publishing, 2020). He has previously appeared four times on the Words for the Wild website.

Allen Ashley – Unwanted

Unwanted

Put on a fake smile,

gush thankfully, “It’s just

what I wanted.” Already

planning to secrete

it at the bottom

of the wardrobe before

seeing if Sue Ryder

or British Heart

will take it off

your pale hands.

Concentrated smile, fierce

attention, this is your specialist

event and really

you should be in

the medals if you pull out

a personal

best performance

on the local sand track

in front of a tiny

crowd in the rain.

Set. Go.

Put on a brave smile

try to take in the details

of shadows on X-rays

and worrying blood

tests and biopsies

added to a cluster

of symptoms that befell

your father, your mother, your

uncle. It’s a gift.

From biology. No

surprise, it runs

in the family.

Allen Ashley

Strawberry Girl by Allen Ashley

The Teatime Tarzan by Allen Ashley

Greetings from the British Countryside by Allen Ashley

Gordon Peters has published a pamphlet of poems, By Leaves Entwined [Jaggnath, 2012] and contributed to various collections such as Remember [by Paragram], and How Big is Your Wingspan [Otago University]. He hails from Moniaive in Scotland and has spent a working life as a social worker, academic and social services director before many years as a consultant in health and social development overseas. He lives in north London.

Gordon Peters – The Gift

The Gift

He came in by chance

but how do I know that?

After all, I carry on not taking

the road not taken,

whereas when he puts one foot

glidingly after the other

then sits on haunches,

stares with silent seduction,

walks till he meets the rug,

snouts the tassle into a bundle,

then lies with chin resting

in that Zen pose,

who is to say how he chose.

Now he is always there.

Never fretful, often hungry,

lavish in comfort,

mean in moving,

an expert in nudging

and wordless communicator

who lives

in the realm of the senses.

We are the ones who feed and upkeep

yet he gives the most

and is mostly asleep.

Gordon Peters

Buffy Shutt lives in the San Gabriel mountains near Los Angeles where she writes poetry and short fiction. A two-time Pushcart and Best of the Net nominee, her work appears in Lumina, Whatever Keeps The Lights On, Rise Up Review, Dodging the Rain, Split Lip Magazine, Anthropocene, What Rough Beast. She was awarded the Cobalt Review’s prize for their baseball issue.

Buffy Shutt – We Won’t Say Too Much About The Hats

We Won’t Say Too Much About The Hats

I want a friend like Florence Merriam Bailey.

She pushed everyone around in

the gentlest of ways.

How else could she have stopped

the murder?

How else could she have convinced

women to stop decorating their hats

with bird feathers?

Five million birds every year—

five million—

were killed for

plumage.

Instead of killing

she suggested we watch birds.

Even in this she was gentle.

When watching birds, she said

no need for a

lion’s roar of technical terms

no raging dullness

just proceed to some

birdy place and

sit and listen in

silence.

Florence Merriam Bailey

stopped murder

and started birding

though there is some man

more credited

with suggesting

we go to birdy places

to watch.

His book was too heavy

to carry into the next room

let alone into the field.

All that is needed

Florence Merriam Bailey gently insisted is

a scrupulous conscience, unlimited patience, a notebook,

and an opera-glass.

The three will do if the opera glass is lacking.

Buffy Shutt

Xiaoly Li is a poet, photographer and computer engineer who lives in Massachusetts. Prior to writing poetry, she published stories in a selection of Chinese newspapers. Her photography, which has been shown and sold in galleries in Boston, often accompanies her poems. Her poetry is forthcoming or has recently appeared in American Journal of Poetry, PANK, Atlanta Review, Chautauqua, Rhino, Rockvale Review, Cold Mountain Review, J Journal and elsewhere. She has been nominated for Best of the Net, Best New Poets, and a Pushcart Prize. Xiaoly received her Ph.D. in electrical engineering from Worcester Polytechnic Institute and Masters in computer science and engineering from Tsinghua University in China.

Xiaoly Li – The Village Girl

The Village Girl

Ning, my high school classmate, and I

choose the highest peak,

to cut bushes for cooking.

The six-year-old daughter

of our assigned family

volunteers to guide us.

The cliff so close,

right in front of us, yet

so far that we are only

half-way there

in half a day.

Gasping in the summer heat,

we reach the top

on our hands and knees.

Waves of ridges flood our eyes.

Too steep and rugged

to go back the same way

we wonder why we even tried.

“I want to go home,”

the girl sits down and sobs.

On my back, I carry the girl.

Ning, the bundle of brush.

We start to descend

the rocky side.

“Don’t forget that sickle,”

the girl points to the high grass,

“It belongs to the village,”

as tears roll down her eyes.

I slowly squat down and

pick up the cutting tool.

Ning tests the road

I follow her every footstep.

“I want my mother,”

the girl whimpers

and the sun disappears.

I hand the girl the one

watermelon candy in my

pocket. She licks once,

twice, then rewraps it and

puts it into her pocket.

“Yummy. I have to save this

for my little brother,” she smiles,

“we’ve never had candy, before.”

Ning and I stare at each other,

wordless.

Xiaoly Li