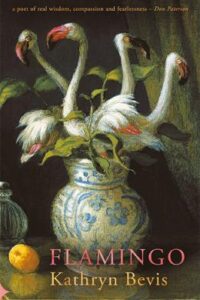

Kathryn Bevis’ debut pamphlet Flamingo was published by Seren in October 2022.

Flamingo by

Kathryn Bevis

We are delighted to have had the opportunity to interview Kathryn about Flamingo and also to hear her read a poem from the pamphlet.

Let’s see what Kathryn has to say.

You make an assertive start, hitting us with ‘Wonder Woman Questions Her Status as a 70s Symbol of Female Empowerment’. It’s a funny, witty call to arms with so many startling images. What made you begin with this poem?

As with so much of this pamphlet (including its title), I followed the advice of Jonathan Edwards who mentored me. He advised a “kick-ass, rip-roaring opening” to the pamphlet and suggested this poem.

Your imagery is stunning throughout the book. Do these surprising, sometimes disconcerting, images come at you out of the blue in a visceral way where you’re compelled to write them down, perhaps you’re at Sainsbury’s checkout or swimming in the sea? Or are they more likely to arrive when you’re staring out the window with a notebook on your lap?

What a great question! I work really hard on imagery and find it one of the most satisfying things about writing poems. Sometimes a comparison announces itself straight away, like that image in my poem ‘This’: “Here, the wind toys with leaves like loose/change in the pockets of the sky.” Often, I have to work harder and list potential images, picking the strongest ones for the poem. I did this with ‘The Darkening’ – taking months to think about forms of light, including “Lighthouse beams refused to stroke the sea to sleep./Whole tower blocks played dead, their pupils blown.” At other times, I play poetry games to generate unusual images: I often ask myself questions like this: “If this x was a song/part of the body/building/garment (etc), which song/part of the body/building/garment would it be?” For ‘Wonder Woman Questions her Status as a 70s Symbol of Female Empowerment’ I generated lots of images in this way, mainly comparing the character’s body and parts of her body to food. In turn, this enabled me to find a satisfying volta in the final stanza.

There’s fury in some of these poems, there’s also huge tenderness and images of intense beauty. Do you ever feel shocked by what you’ve written?

Often. I think if that shock doesn’t happen as I write the poem, it can’t possibly happen for my reader. Writing poems has definitely helped me to exorcise a few demons, too. To make art out of something painful, uncertain or damaging is an act of real empowerment.

The shape of a poem is obviously important to you, for example in the exquisite and moving, ‘In which I imagine my aborted foetus sings to me’. I wonder, what was your intention here with this spacing? On a visual level, the spaces seem to me to be like running stitches.

After writing the first few drafts of this poem, I knew I wanted it to be a sonnet, even such a deconstructed one, as it was written in love. The spaces are there partly for movement, partly as a musical notation to indicate pause and breath, and partly to act as the poem’s punctuation. As it’s written in the imagined voice of a foetus, by definition a being not fully formed yet, I wanted that feel on the page, too.

Your poems are published as a pamphlet, your book is out, how do you feel now that the poems are in the hands of readers? Do you trust readers with your poems? Do you feel free of the poems? Or are they abandoned; do you not care about them now that they’re out there?

Quite a few of the poems are a couple of years old and I feel that I’ve done my best with them. Rather like sending a teenager off to university, I think they need to go out there and take their own chances in the world, now! The five poems which conclude the pamphlet, those that tackle love and mortality in the face of a life-limiting diagnosis, are different. They’re very fresh and important to me. I was lucky to have such an understanding publisher in Seren, and two great editors in Zoë Brigley and Rhian Edwards, as they allowed me to swap out some older work at the last minute and substitute these new poems.

On the whole, I tend to be concerned with the work I’m writing now, the poems which reflect my current concerns and passions, rather than what’s getting published or being given a platform from the back catalogue. If the older poems do well and find a good pace to roost, great, but that doesn’t give me nearly the pleasure that the creative process does.

In ‘starlings’, I love how you’ve created the language of starlings, and even the language of flight, using the language of prayer. It is as if a starling priest is speaking. It is extraordinary and original, and almost as if we’re flying with them. Did it arrive with this sense of chanting incantation? Do poems come to you as sound or perhaps as rhythm? Do you hear poems?

Thank you. In ‘starlings,’ I was responding to a Richard Evans poem, ‘Murmuration’ which won 2nd prize in the Winchester Poetry Festival in 2019. I love that poem so much I was drawn to respond to it in a direct way. In terms of the religious language, I shamelessly ripped off the cadences of the Bible, particularly Tyndale’s beautifully poetic translations of the opening chapters of Genesis and the gospel accounts of the sermon on the mount.

I always hear poems and read them aloud as I draft and redraft them again and again, learning them by heart. That way, I can hear where the duff notes are. I’m a huge fan of editing: making a sow’s ear into a silk purse by writing dozens of drafts. In each one, I’m listening as hard as I can to the poem’s soundscape and learning by feel in which direction it wants to lead me.

You’re unafraid to dip into many pools of language, and to use many distinct voices and moods. Again, I’m wondering, is this something you hear or perhaps make a decision on later in the editing process?

I’ve always found poetry exciting because it can allow you to do, be, and say almost anything you want. The poems I love the most by other poets are often mash-ups between two distinct linguistic registers: Joanna Ingham’s use of mathematical language when writing about maternal love in ‘She tells me she loves me till the last number and what is the last number anyway?’; Di Slaney’s use of a word hoard with Germanic and Anglo Saxon origins to write about the human and pre-human stories underlying a specific place in ‘History of a Field’; and the glossary of climbing terminology used to paint a loving portrait of a grandparent in Andrew Waterhouse’s ‘Climbing my Grandfather.’

I’m also obsessed with poems that shapeshift, allowing their speaker to become an object, place, or creature. I tend to respond to poems I love with ideas of my own and that’s often the genesis of my creative process.

It’s a cliché to call a group or collection of poems an emotional journey but this is an emotional journey like no other. Near the middle we go from the comfort and thoughtfulness of ‘Anagrams of Happiness’ to the disturbing ‘Teddy’ and ‘The Smuggler”. These emotional steps are curated with great skill and attention. How do you read a pamphlet or collection? Is it important to read in the order prescribed by the poet? How much pleasure does poetry give you? Which poets inspire you?

I think a poetry pamphlet can be either a mix-tape or a concept album and I’ve read great examples of both. For me, while there was no overarching narrative for this group of 25 poems, it felt important to include a balance of light and dark and to group the poems, where possible, by theme.

It’s important to think about the journey you take your reader on and how you keep her or him safe along the way, especially when tackling emotionally challenging material.

In terms of my own reading, I tend to dip into longer collections and gobble pamphlets from beginning to end. For me, reading poetry is always about the pleasures of connection and craft. Some of my favourite poets currently include: Joelle Taylor, Vicky Morris, Caroline Bird, Jonathan Edwards, Kim Moore, ASJ Tessimond, Carol-Ann Duffy, and Simon Armitage.

So many birds are flying through your poems both as subjects and as imagery. But never in the way one might expect. What is it about them?

Ha! I honestly don’t know. I listen out for birdsong and love watching birds in flight. I also dream a lot about flying when I’m asleep. I think I share this obsession with a lot of other poets, past and present.

The body is evident throughout the pamphlet, as in, for example: ‘In this poem, your routine bloods have come back normal’ and ‘My body tells me that she’s filing for divorce’. Both are astonishing and beautiful poems but devastating in the way we meet illness and mortality with boldness, wit and originality. Similarly in ‘The Butterfly House’ and ‘How Animals Grieve’, this addressing of mortality, confronting it head on strikes me as extraordinary and fearless. Is writing a poem ever easy for you?

Thank you for this question. Every poem I write makes different demands on me: ‘My body tells me that she’s filing for divorce’ for instance, came simply, almost whole, straight after my diagnosis and – oddly – gave me great pleasure to write. ‘How Animals Grieve’ was a much longer process and needed dozens of drafts, plenty of feedback from poets I trust, and a complete revamp of the poem’s framing device in the first and final stanzas.

Because I’m autistic, I have an unusual way of looking at events and experiences, as well as a direct way of communicating about what’s important to me. That’s been true for my writing about cancer and living with a life-limiting condition as it has for my poems about love, feminist concerns, schools, and the beauty of the living world.

Truth and beauty are to be found everywhere in this book. Sometimes funny, sometimes very sad, always witty, interesting and original, it is hugely impressive and an enormous pleasure to read; needless to say, you have left me wanting more. Was it difficult to pick the poems?

It was incredibly easy to pick the poems: I just went for my best 25. It’s taken me a few years to get my poems to the standard I wanted them to be at before publishing a pamphlet. Flamingo came together at just the right time and I was very lucky that the right publishing house picked it up and published it so quickly.

And on a similar subject, rumour has it that your publisher would have liked a full collection but you declined. Is that because these poems form a narrative of their own? What is the difference between putting together a pamphlet and a collection?

Ah, rumour! I was endeavouring for each poem in the pamphlet to be what my fellow-poet and friend Vicky Morris would call “a banger” rather than publish more poems which weren’t of the same quality. I haven’t had the experience yet of putting a full collection together but watch this space. Because of the intensity of life I’m experiencing now as a palliative care patient, I believe that what’s coming next will have a stronger, overarching theme.

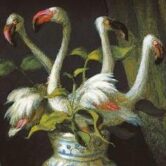

The book ends with the beautiful, devastating, surreal title poem, ‘Flamingo’. Our readers will have to read the book to know what’s actually going on with these big birds but what I will say is that the poem resonates beyond itself and with that final phrase, you’ve left us wondering. I actually don’t want an explanation of that phrase, please, I prefer to allow the thoughts it conjures to reverberate through the empty halls of my mind. Was that your plan?

Flamingos have the most incredible mating ritual where they dance with and for each other (seriously, take a look at it on YouTube: it’s beautiful). Part of being in love with Ollie is wanting him to find someone else to love and share his life with when I’m no longer here. That last line, the whole poem really, is an explicit act of blessing for him to find someone else to love and be loved by after I’ve died.

Very many thanks, Kathryn, I wish Flamingo and you huge success.

Thank you, Amanda.

Flamingo

Kathryn Bevis is founder of The Writing School Online and was Hampshire Poet 2020-21. She is the Selected Poet for Magma’s Solitude issue and her poems have appeared in: Poetry Review, Poetry Wales, Poetry Ireland Review, Mslexia, and The London Magazine. In 2022, she won the Mairtín Crawford Award for Poetry, the Poetry Society Member’s Competition, and the Second Light Poetry Competition (first and second prize); coming second in the York Poetry Prize and the Edward Cawston Thomas Prize. Kathryn teaches Poetry for Wellbeing courses in mental health and substance-misuse recovery settings, and prisons. She’s working towards her first collection.

My body tells me that she’s filing for divorce

She’s taken a good, hard look at the state

of our relationship. She knows it’s not

for her. The worst thing is, she doesn’t tell

me this straight up or even to my face. No.

She books us appointments with specialists

in strip-lit rooms. They peer at us over paper

masks with eyes whose kindness I can’t bear.

They speak of our marriage in images:

a pint of milk that’s on the turn, an egg

whose yolk is punctured, leaking through

the rest, a tree whose one, rotten root

is poisoning the leaves. I try to understand

how much of us is sick. I want to know

what they can do to put us right. She,

whose soft shape I have lain with every night,

who’s roamed with me in rooky woods, round

rocky heads. She, who’s witnessed the rain

pattering on the reedbed, the cut-glass chitter

of long-tailed tits, the woodpecker rehearsing

her single, high syllable. How have we become

this bitter pill whose name I can’t pronounce?

Soon, she’ll sleep in a bed that isn’t mine.

That’s why, these nights, we perform our trial

separations. She, buried in blankets, eyelids

flickering fast. Me, up there on, no — wait —

through the ceiling, attic, roof. I’m flying, crying,

looking down. Too soon, I whisper to her warm

and sleeping form. Not yet. Too soon. Too soon.

Kathryn Bevis