Alan McCormick lives with his family by the sea in Dorset. He has been writer in residence at Kingston University’s Writing School and for the charity, InterAct Stroke Support. His fiction has won prizes and been widely published, including Salt’s Best British Short Stories, The Sunday Express Magazine and Confingo.

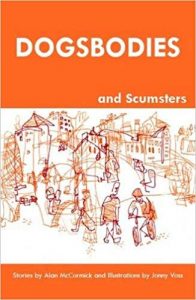

He also collaborates with the artist Jonny Voss, where their work featured regularly on 3:AM Magazine. ‘Reasons to Swim Inside the Sky’ comes from their book, Dogsbodies and Scumsters, which was long-listed for the 2012 Edge Hill Prize.

See more at: www.dogsbodiesandscumsters.wordpress.com.

Jonny’s work can be found at www.jonnyvoss.com and www.jonnyvossart.blogspot.com

Art by Jonny Voss.

Reasons to Swim Inside the Sky

Alan McCormick

The canals of upper Clapton are mustard smelling trenches of blink-and-you-miss-it spasm splatters of colour amidst tar dark pathways. Bushes bristle with broken bottle leaves, mottle cast in a sullen, diesel pallor. Warrens snake under daisy field enclosures, as rabbits jump up into patchworks of butterfly pastures in green shield stamp grasslands. Silence only broken by the magnetic hum of telegraph wires slung from giant cranes, barbing and scratching the clouds in criss-cross lines: steely map gradients for a slate grey sky.

A mugger’s paradise – yellow raven’s eyes peep through black balaclava pillbox heads, bronchial and hoarse against the damp thin wool – lone men lurking in barbwire crevices, torsos immersed in the marshy reed vines, aqualungs of bile and blood coursing from their veins. Punctuating a walk along the bank are police notices with fish and chip paper headlines – uptight black letters stuck like calcified felt on crude yellow metal boards – milestone millstones chronicling acts of predatory violence.

Barges rest up along the River Lea decorated in Nepalese colours – mud reds, indigo and ochre. A local pub by a redbrick council estate spills people out into the early summer evening. Misplaced pudding-faced walkers, urban and ashen skinned, clutch their pints and look out to wide savannahs of wire sharp grass that grow beyond the swamp reeds of a still distant marshland. Chewing the crisp packet fat over memories of long distance walks: exaggerated escapes from concrete chokey and unlikely fishing exploits and tips swapped and passed on: ‘put Perrier in this canal and you could oxygenate the dead.’ Fish rise like aquiline Christs from sunken tramways set beneath the fine silt bed. As if on cue, a salmon with a display of temper cruises by, belly up, rung free from its cellophane tomb wrap (courtesy of the local Tesco Superstore) – a smile of slash gut, a grinning fish coyote, its scaly skin shimmering silver and purples amongst the petrol whirl-wash of slow moving water.

You’re as likely to see a discarded shopping trolley or a deserted desert boot as any living being float upon this surface; but there are lovers here. Lone couples circle in the fringes, promenading the mud banks. Held close on one side by the claustrophobic, crumbling outskirts of the city and on the other by fields of secret kisses calling, blush tinged in the spreading sunset – the promised melt of soft lips joined. They walk in twos like swooning Bobbies on the beat; their fingers interweaved behind their backs. Dusk is their time to take the air, now momentarily sweet, before the sun floats down to disappear and the evening draws in and closes out the light.

Swans form couples too, but one swims alone: Tony, named after a long-necked former defender of these parts, Tony Adams. He moves with a ferocious glandular reputation to live up to; encased in a brick-hard armour of snow pelt, he hisses like a tomcat if you get too close.

Downriver on the bank, the famous Dalston Heron poses on stilt-like old man’s legs. He is as still as night and cranes his telescopic neck and haughtily gives the eye, his calm shape-shifting in the shadows, his presence benign and balanced, somehow comforting. But a raucous bellow of noise comes from a pub and he takes his uptight walk and moves away.

A group of red faces nestled together on pint filled tables jab their tongues and shout out the odds. And from there comes a small boy, escaping his drunken mother’s shackles, emerging between heavy adult legs, and rubbing at his eyes. He moves towards the heron, which stands quietly by a wall, its feathers blurring in the breeze. The boy reaches out with his hands and the heron lays his long, red bill gently on the boy’s shoulder. And they find a space, air cuddled in between, and slowly rock: a melancholic waltz. From the aggravated throng splinters a shard of angular spite: ‘Sean, where the fuck are you?’

Bobbing close by, like a small balsa wood boat, is a protective coot who blows his tiny soul trumpet through a Burger King straw – Zoot the Coot, whose shrill call-melody seems to rest on the woman’s pitch each time she cries out. ‘Sean!’; blast of coot; ‘Fucking hell, Sean!’; more blast of coot until the boy and the heron are suddenly gone, and all is quiet again.

In a park, a small red vixen slinks into the bushes where her family waits. The moon passes shadows and light between the clouds, as the night rolls softly on the velvety, ebbing sheen of the canal. And there, high on the grass, are the boy and the heron – suddenly lit, finding places to hide and spotlights of moon dust to play and emerge into. The heron is watchful, standing proud, as the boy runs down a slope, his arms flapping through the air.