Rachel Beresford-Davies grew up in Hong Kong and has since lived in London and the south of England. She has two science degrees and is currently studying for an MA in Creative Writing at the University of Winchester. She has been writing for many years but mostly kept it to herself. In the last year though she has had short stories published through Fairlight Books and Literally Stories. Her writing is mostly inspired by the everyday and commonplace events she observes in her mostly everyday and commonplace life.

Satsuma

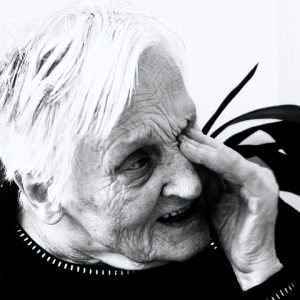

Mother is sitting on her sofa peeling a satsuma or clementine, or some other small, orange citrus fruit. She has removed the skin in small, fingernail-sized pieces, and is now carefully detaching quivering strands of pith, and placing them with precision next to the teetering pile of skin on the arm of the sofa. I will be clearing it off later.

After removing as much of the pith as she is able she will eat the satsuma or clementine or whatever it is, chewing each individual segment with the three teeth she has left in her mouth and extracting the juicy orange flesh from inside the translucent membrane with her tongue. Then, one by one, she will remove the fleshless membranes from her mouth and place them with the pile of skin and pith.

When she has finished this process, which normally takes around thirty minutes, she will sit for a time, turning now and then to look at the pile of skin, pith and membranes, perhaps rearranging them a little. Very occasionally she will carefully gather the pile of detritus and place it on the coffee table in front of her, where she will sit for some further time, regarding it judiciously.

Eventually, she will shuffle forward on her seat, and with some effort stand up and walk over to the fruit bowl where she will spend some moments selecting another small, orange citrus fruit. Thus the entire process will be repeated, ad infinitum should the fruit supply allow.

I have learnt to pace the small orange citrus fruits. Four for the morning, four for the afternoon, or occasionally, on a bad day, five. None for the evening. In the evening she will doze, lulled by the clatter of family life and television drama. But during the day, it is just her and I, and neither of us sleep.

She has eaten the final fruit of the afternoon and is agitated. It is only 4 o’clock. There are countless more small, orange citrus fruits, hidden under the stairs. Her netted pacifiers. Glancing up now and then as I tap at my computer, I silently observe her, hovering beside the fruit bowl, now and then grasping one of the apples before putting it back. She cannot eat apples, her three widely spaced teeth will not allow it. She knows she cannot eat apples, yet she doesn’t know who I am.

I sigh, and look past her, fixing my gaze out of the window on the disordered back garden. The grass is barely visible, covered with an untidy blanket of fallen leaves in russet and yellow, making the lawn look like an unmade bed. Every now and then the wind whips up and swirls them in circles, depositing them again a few feet from their last resting place. They seem to have caught mother’s attention too and she turns her frown from the fruit bowl to the window, making small, indecipherable sounds. I go over and stand next to her for a while, hoping to calm her agitation, and together we watch the leaves dance soundlessly about. Eventually though, her sounds become more urgent and threaten to become something else. I gently take hold of her arms.

“Come and sit down mum. Do you want a cup of tea?”

Her previous cup of tea stands untouched on the lamp table. But then, there were satsumas. Now, there’ll only be tea. It might work.

She submits and allows me to guide her back to the sofa, still mumbling. She sits for a while, her hands fidgeting in her lap, casting confused looks at the fruit bowl.

Suddenly, she turns her head towards me and says, clear as a bell,

“Where’s Gerald?”

She does this sometimes. It is as if somebody has flicked a switch in her brain causing random connections to be made. They will sputter out again soon enough, but I always enjoy her rare moments of apparent lucidity. This one though is unexpected, and for a moment I am floored. Gerald – my father, her husband. Gerald, who cared for her, clearing away the endless piles of satsuma peel, finding them in unlikely places. Gerald, hollowed out from the loss of our family’s anchor, chuckling as he reported her antics.

“I found a pile of peel in the fridge the other day,” or, “she’d managed to tuck some down behind the cistern. I mean, why does she need to hide it?” And we’d laugh, tears pooling in our eyes. Together we mourned who she had been and tried to seek comfort in what she had become. “She’s as strong as an ox, your mother, she’ll survive all of us,” he’d said after her diagnosis, “trouble is, it’s your heart that keeps you alive, but your brain that keeps you living.”

It was the former that finally claimed him, leaving me the sole clearer of satsuma peel. I stir mother’s tea and take it over to the sofa, collecting the waste paper bin en route. Mother is still looking at me, but I can see she has already forgotten her question. “What did you say, mum?” I ask, just in case, placing the cup of tea next to her. She frowns and turns her gaze slowly on the fruit bowl. Once again, she begins to shuffle forward on her seat. I scrape the satsuma peelings from the arm of the sofa into the bin, watching them fall among the accumulated others, slowly rotting at its base. They are like the fragments of her brain. Disease-ravaged, being whittled away, cell by cell, with every satsuma she eats.

I turn on my heel and head to the cupboard under the stairs, extracting two bags of satsumas. The netting cuts into my fingers as I rip them both open, and tumble all sixteen small, orange citrus fruits into my mother’s lap. “Do your worst, mum,” I say. She looks down, and just for a second or two her face is lifted by something that could almost be joy.

Rachel Beresford-Davies